espresso

by Paul Christopher Johnson

[Editor’s note: this article is mirrored from the Social Science Research Council online magazine frequencies, published 2011 09 29]

We have been up all night, my friends and I, beneath mosque lamps whose brass cupolas are bright as our souls, because like them they were illuminated by the internal glow of electric hearts.

F.T. Marinetti, “The Futurist Manifesto.” Le Figaro, February 20, 1909.

Anselm defined God as a being than which nothing greater can be conceived. This is never the case for the ultimate demitasse of espresso, known as the godshot. Occasionally a godshot is reported, a triumph of technique, technology, and nature. But mostly godshot suggests deferral, a perfection yet to come. Prospects of better gear, superior beans, purer metals, and more advanced knowledge fire the imagination of finer versions, an espresso to produce still more intense experiences of taste and stimulation, a truer sense of terroir and origins. It is just over there, and we can taste it. Espresso mediates, and is used to transform, the relation between subjective experience and the external world. The most valuable coffee bean ground for espresso, Kopi Luwak, is collected after being ingested and excreted by Indonesian civets. Now that’s a spiritual food, beans chock-full of inner life, and the potential of its expression.

Though the nomenclature of the godshot may be said to be mere semantics, semantics are rarely merely mere. The recent expansion of third-wave coffee conoisseurship and technologies, producing myriad new and reformed public shops and cafés (McCafé in the Golden Arched Holy of Holies), and ever more accoutrements for the home, is dramatic. In this short flight, I explore spirituality through espresso, as a history of exchanges between people and machines that brokered, adjusted and defined the relation between outer and inner, between external “things” and inner experience.

Coffee beans are, of course, the produce of a plant, not precisely a thing. They are even actors of a sort—enliveners, vivifiers, catalytic converters. Their origin legend tells of an Ethiopian goatherder boy named Kaldi who, in the tenth century (or eighth, or fourth, or seventh) first observed the excited behavior of his goats as they gnawed wild berries, and decided to try the same. The stimulating force of coffee was always a major part of its appeal, albeit in diverse ways, from its emergence in Ethiopia to its systematic plantation in Yemen to its global transport via the expansion of Islam and then the Ottoman Empire, to the arrival in Europe via Turkey in the hands of Venetian traders, to the first coffeehouses of Europe by the mid-1600s. Those seventeenth-century “penny universities” arrived just in time to help produce the public sphere, and to construct diagnoses of the secular that poured from the chatter over cups. Etymology presents a similarly global arc—English coffee from Turkish kahve, from Arabic gahwa, abbreviated from gahwat al-bun, “wine of the bean.”

The nominative tether to that more famously spiritual food, wine, is suggestive. Wine has a long pedigree as a thoroughly religious sort of drink, from Dionysian to Christian rites, and in metaphysics from the Symposium to the theory of transubstantiation. Roland Barthes called wine the totem-drink of France. Wine not only represented France the nation, it also converted its subjects into citizens. As a converting substance, wine miraculously extracts opposites from its object: youthfulness from the aged (as Socrates says), and boldness from the shy. Wine is of the earth, producing not only the bacchanal but also dreams and reverie, a theme addressed in depth by Bachelard. For some, wine’s spirituality has to do with its indigeneity, the inseparability of its identity from particular lands, as terroir. Other writers, like Michel Leiris, found in it the dread of the alloy, the blend, the complete interpenetration of one thing by another. Wine and water, like coffee and milk, can completely fuse, connoting the horror of the total breaching of boundaries and loss of identity, an unavoidable risk of conversion.

Other familiar ingestibles that modulate interior human experience in relation to the material world have been addressed in spiritual terms too. Fernando Ortiz’ masterpiece, Cuban Counterpoint, juxtaposed sugar and tobacco:

Food and poison, waking and drowsing, energy and dream, delight of the flesh and delight of the spirit, sensuality and thought, the satisfaction of an appetite and the contemplation of a moment’s illusion, calories of nourishment and puffs of fantasy, undifferentiated and commonplace anonymity from the cradle and aristocratic individuality recognized wherever it goes, medicine and magic, reality and deception, virtue and vice. Sugar is she; tobacco is he. Sugar cane was the gift of the gods, tobacco of the devils; she is the daughter of Apollo, he is the offspring of Persephone.

Ortiz insisted on the spiritual dimension of these ingestible things by pointing to their resemblance to religion proper: “The smoke that rises heavenward has a spiritual evocation … like a fumigatory purification. The fine, dirty ash to which it turns is a funereal suggestion of belated repentance.”

Those religious resemblances are less intriguing to me than Ortiz’s approach to spirituality through material, edible things, his poetic exploration of the techne (in Heidegger’s sense of technique plus poiesis: methods of causing to emerge) that people apply to building correspondences between inner and outer worlds, however construed. “Spirituality” refers to the practices and things used to find and make more or less direct ties between subjective experience and the shared empirical world. For Kant or Durkheim, spirituality is strictly impossible—and quixotic—since the world is irremediably mediated, refracted and translated via symbols. Spiritual practices, contrariwise, enact the possibility of a real and direct fusion of the self and the world. It was in this sense that Henri Bergson, Durkheim’s schoolmate and peer, was called a spiritualist, sometimes derisively, since he posited the direct experience of the world through what he called Intuition.

Spirituality from this perspective is but tangentially related to “religion.” It can take more or less religious forms, in the sense of mapping correspondences between subjective experience and the external influence of gods, but it need not be religious in that restricted sense at all. In spirituality’s most intense expressions of direct internal-external, subjective-objective mappings, it can verge into something like shamanic magic, the use of private visions to exert even causal power on the outside world; raising the sun, say, or healing another’s body. In its softer, more secular and more consumerist forms, spiritual practices seem to produce a more or less barometric idea of interiority, in which inner states are felt and presented as meaningfully indexed to the outside world—the melancholy that mirrors, and even takes part in, the rainy day. Bergson the “spiritualist” used the example of the feeling of impatience he felt as he waited for sugar to dissolve in water he wanted to sweeten. The fact that he must wait is, he wrote, “big with meaning.” As the sugar’s time to dissolve and his impatience are merged, the sugar-water is conjoined with a piece of his own life’s duration, producing a fullness of time that we only artificially parse out into segments. This fullness is the Whole. Later he called it the Duration.

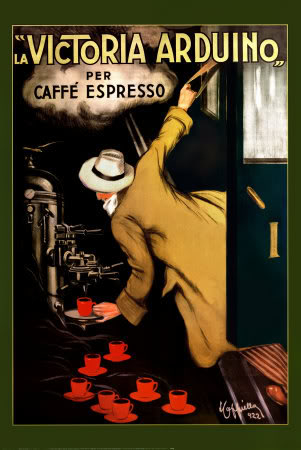

It is surely not incidental that Bergson was terrifically concerned to remind readers of the Whole and the Duration at just the fin de siècle moment when machines that transformed and transmitted nature at ever-accelerating speeds were also increasingly mediating peoples’ relations to each other, to the world, and to the experience of self. Espresso machines were one of many innovations that came from harnessing the power of steam—steamships, steam locomotives, steam coffee. The earliest contraptions forcing water through tightly packed coffee grounds using the force of steam were built in France in the early 1800s, employing a rough technique that remains in use today in almost all Italian homes in the stovetop moka pot. The espresso machine referred not only to the new technique of making coffee at pressured speed—the same word was applied to fast-traveling trains, for example—but also to individually prepared servings made expressly for one customer. The early machine-builder and entrepreneur, Victoria Arduino, joined the images of the speeding train and the steaming new coffee served for the on-the-go solo customer, in a striking 1922 advertisement drawn by Leonetto Cappiello:

The first brass pressure machine was Italian, made by Luigi Bezzera and Desidorio Pavoni between 1901 and 1903, and it was mostly Italian machines that filled the art nouveau cafés of Europe’s belle époque. Bezzera probably built the basic machine, but it was Pavoni who first marketed the name, “espressso,” and also Pavoni who first attached the wand that released surplus steam and later allowed for the theatrical fashioning, and then the fashion, of foamed milk drinks like cappuccinos. Early lever-pump machines were also Italian, built by Giovanni Achille Gaggia in 1945, using a spring-piston design to increase the pressure brought to bear on more finely ground coffee. The pressure generated by Gaggia’s machine created the crema that became the signal feature of correctly made espresso. These Gaggia-made espressos with crema and foamed milk were the drink that sated the post-war boom in the cafés of Europe, filled to bursting as rations on coffee were lifted and public life revived. Many of the art nouveau and deco cafés, at least in Paris, look much the same today as they did in Bezzera and Pavoni’s time. The solid, dazzling espresso machines of polished copper, brass and steel are still manufactured as a retro-look today, and they afford a sense of the aesthetic effects they must have made on patrons a century ago: Sleek, angular metal set against lush velvet in elegant cafés, industry tamed and polished, steam-locomotion civilized in the salon, piston progress welded to fashion and desire. After the Second War, espresso became totemic, sharing with wine, tobacco, and sugar the status of what Barthes called “converting substances.” They were bio-technes to cultivate desired relations of interior states with the external world, or even occasionally blurring them, as in the unmediated Whole of the godshot.

Still, what could be “spiritual” about the espresso brewing process itself? At first glance, this looks like the opposite of the spiritual, more like a story of industry, speed, efficiency, of workers’ schedules that required 25-second rather than minutes-long extractions for their quickening, of standing at counters rather than sitting at table, of white European masters pressing still more energy from brown tropics, of power, and Italian nationalism; in short, about control. Maybe even, kind of, about fascism, the brass and steel, eagle-topped machines that yoked the totemic drink to striding national aspirations? F.T. Marinetti, the early bard of Italian fascism, included in his 1932 Futurist Cookbook dishes made with espresso, like “The Excited Pig”: A whole salami, skinned, then cooked in strong espresso coffee and flavored with eau-de-cologne. Surely this sort of techno-industrial orgy was the opposite of the spirituality of wine or tobacco, of conviviality or reverie or dreams or intuition or the Duration.

Yes, yes, yes… and yet. This is “spirituality” too, pipes and ducts traversing interiority and exteriority using metals and steam and technique, not to mention, of course, the giant southern storehouse of beans yanked suddenly much nearer through the power of steam, the steam of ships, rail, and coffee. As the flipside of romantic spirituality, here was a precursor of the cybernetic spiritual, the holy machined human as a fusible sequence of evercharging parts. Marinetti wrote in yet another manifesto, “The Futurist Sensibility” (1919): “Instead of humanizing animals, vegetables, and minerals (an outmoded system) we will be able to animalize, vegetize, mineralize, electrify, or liquefy our style, making it live the life of material.” Animalize, electrify, liquefy: espresso was a steam-arm prosthetic with which Kaldi the Ethiopian goatherder boy of the mythic origins of coffee, after a thousand years of imitation and approximation, finally became the ecstatic goat, dancing in the Duration.

The ecstasy of the electrified and liquefied individual soul is not the only conversion espresso achieves. Parisian cafés, for example, offer an alternative to mediating the self with spiritualities of speed or solipsistic reverie. Here, inner experience is mediated by espresso in hyper-social style, and Durkheim smiles from the cemetery of Montparnasse. Café tables are filled three-rows deep before you can even get inside. The chic and the hoi polloi alike are gathered to gab, look around, and peer over their standard-issue espresso at other people. The bentwood and rattan chairs are always faced out toward the big stage of the street. None are turned inward. Espresso is supremely public and visual, a prop for seeing and being seen.

To the taste of Italian traditionalists and third-wave American and Australian coffee geeks, it is also often careless: Robusta rather than Arabica beans, dosed to fill the order but probably ground awhile ago, and not enough of them, and barely leveled or tamped anyway, and the shot inattentively pulled during a chat with another customer. But not only that! Cigarettes and wine are being consumed alongside espresso, whether at 10:00 am or 10:00 pm. This is quite unlike the rational segmentation of converting substances, time schedules, and kinds of socialization or reverie operative in U.S. public and private houses (caffeine, only until noon; liquor, only after five; cigarettes, I think I saw one in Mad Men once.) The easygoing style of French espresso preparation, and the promiscuous Parisian mingling of espresso, wine and tobacco, ruffles coffee geeks’ view of the solemn focus called for in approaching the elixir. The French barmen are sure to mishandle the proper roast and temperature, the purity of the water, and the microfoam texture of respectable crema. French consumers are likely to overlook the citrus tones or nutty notes, and to misrecognize the overall mouthfeel. Critical connoisseurs arriving from the U.S. or Australia find the beautiful old espresso machines of Paris wasted in flip sociality. For these coffee geeks, tending their spiritual discipline, there is nothing so insouciantly social about espresso. Theirs is more of a Shaker ethos, built on the love of process and craft and tools, and an indivisible sympathy with and through espresso, like Bergson’s intuition of the Whole as he watched sugar dissolve in his water.

Like Bergson, they’ve had a revelation that inspires reform. Walk into Café Coutume in Paris, on Rue de Babylone in the conservative 7th arrondisement, for example. The owners are an international group of third-wave missionaries—Portuguese, Australian, American, and a lonely Frenchman—embarked on the quest to redeem the loose Parisian cafés. They describe them as lost in their old traditions, whereas they take part in the “new coffee culture.” No rattan chairs out front to watch the world go by here. Instead, hanging naked bulbs and lots of luscious metal gear decorate the interior—vacuum siphons, a drip system of beakers, grinders, roasters and, very prominently, a fine red and chrome Italian La Marzocco GB/5 three-group espresso machine. The Strada, the ultimate espresso machine, is “coming soon,” and will be the first in France. (The godshot is near, the Duration is imminent). The gleaming machine is right up front, on display rather than buried behind the bar as in most bistrots and brasseries. Antoine Netien, creator of the café, explained, “The French are more accustomed to things that are more hidden. Our open motif is very American. You can see everything happening.” But it’s also visually focused on the gear needed for the perfect, expressly individual experience, despite the owners’ hope that the new café will be the hub of the promised new culture. Solitary drinkers are common. They are not here to talk, unless it is to ask about the equipment, or to demand intricate espresso drinks of precise individual formulae. Their orders require even an experienced barista’s fixed attention. It’s a good thing they recruited Kevin, from Iowa City, for the job.

September 29, 2011