[Ed: Re-post from April 28 2018]

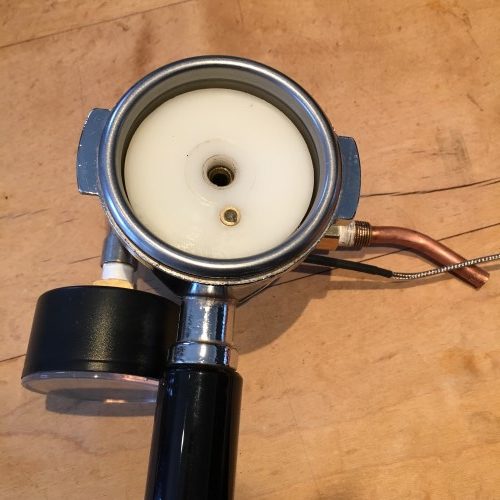

I did pressure profiling partly as an idiot check, but mostly out of curiosity. As I am using the same springs in the old machines and the new group the performance should be the same. The only thing that really needs to be verified is initial/peak shot pressure which depends on the length of the compressed spring with the lever in the down position (and any variation between the actual springs themselves). The method used to do the profiling was laborious. I made my own Scace-type device with an Acetal disk to fill in for the puck, an analog pressure gauge, a K-type thermocouple and, something not featured in the Scace, a needle valve to control the flow.

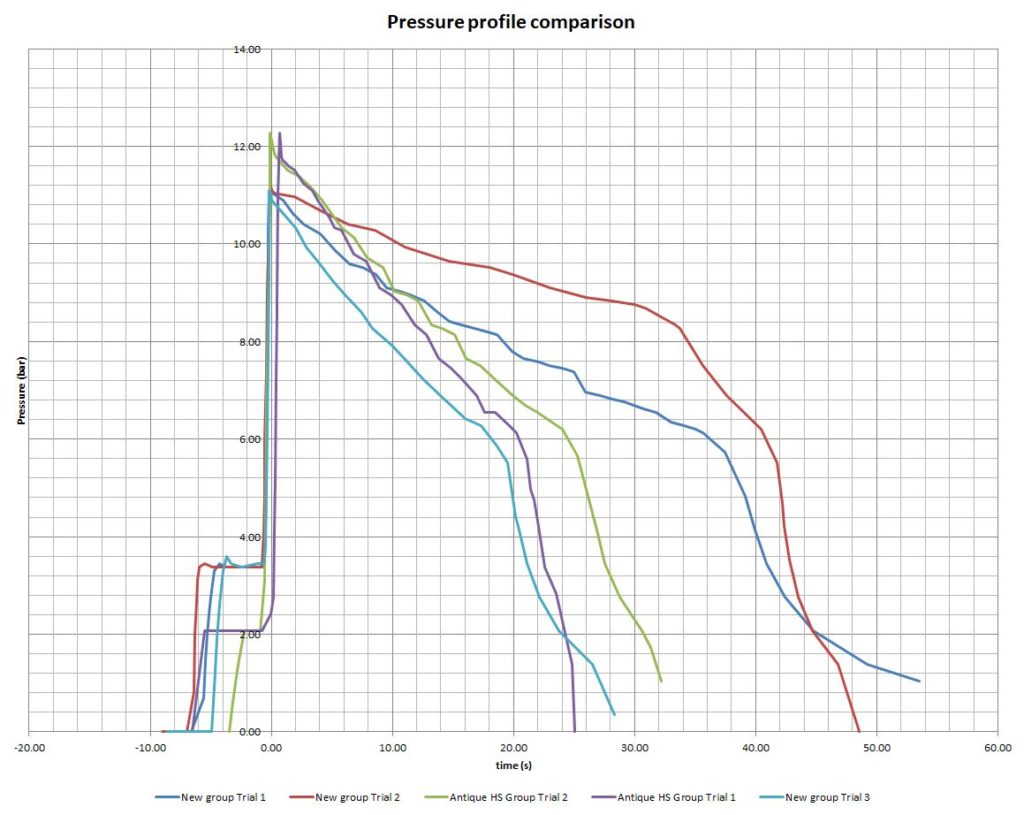

Then I filmed some simulated shots and logged the pressure readings on the video every five or ten frames. Boooooooooooring. There are many better ways to do this, but, as I said before, I don’t really need to check the variation over time, just the steady states. I tested three machines: the 1987 diagonal HX, the slightly earlier horseshoe HX and the new prototype group. However, the results between the two antique machines are essentially the same, so I only bothered logging one of them.

Conclusions:

It is hard to adjust the needle valve to get repeatable flow rates and thus repeatable simulated shot times, but you can see that the spring performance is essentially a straight line from peak to about 6 bar. At 6 bar, the lever reaches the end of its travel (i.e. the spring is completely extended) and the rest of the curve is just residual pressure.

When the lever is lowered, the line plateaus at the pre-infusion pressure: just over 2 bar for the antique machine which has a pressure regulated water supply and a little over 3 bar for the prototype which was directly connected to the city supply.

Peak pressure for the antique groups was just above 12 bar.

Peak pressure for the prototype is about 11 bar – this was adjusted to 12 bar by shimming the spring by about 2mm.