“We stood with our eyes fixed upon those heights crowned with the memories of four centuries of glory, pleasure, love, conspiracy and bloodshed – the throne, the citadel, the tomb of the great Ottoman Empire – and no one spoke or moved.”

Constantinople, Edmondo di Amicis, 1877

Orders for the Lapera DS3, the Constantinople Edition, are now open. The base price for the machine is 9717.17 USD plus shipping. This is a lot by any measure, but not, we feel, and if you understand the process, by any means excessive. You can reserve here. That’s the short of it. For the long of it – read on.

I was fortunate enough to spend several glorious months in Istanbul as a student, studying the architecture and culture and drinking Turkish coffee – my very own diminutive and suitably accompanied Grand Tour1 of the sites of antiquity. One afternoon, as I wandered the back alleys of Eminönü, I stumbled across the unmistakable and, to me, irresistible chewy-toffee smell of roasting coffee. Drawn through an archway into a small courtyard, I discovered the source: a gigantic gas-fired 19th century Italian roasting machine. Aslan, the affable, slightly portly and sixty-something master roaster, beckoned me into the ramshackle space piled to the ancient beams with sack upon sack of green coffee. He opened the hatch on the side of the beast to reveal rows of foot-long thunderous jets of blue flame, fangs in the maw of a dragon. He showed me the process, judging by ear and by eye and by taste, piling little mounds of beans collected with the sampling spoon in a row on a small wooden table next to where he sat. His vast experience gained no doubt as an apprentice to his predecessor, and his predecessor’s predecessor, and his before him. Coffee has been roasted on this spot for over a hundred and fifty years. As the rake turned over the cooling beans he ground a handful of them into a little cone he made from a page of his newspaper, twisted the top closed and sent me back down the alley to have the fine powder twice-boiled in a cezve by the vendor on the corner and served to me, sekerli (with sugar), in a tiny demitasse. Aslan was both affable and devout, he timed his roasts to end just before the muezzin’s call, shutting down the machine and walking through the bustling crowds, past the nut sellers and the spice shops to disappear through an innocuous brick archway between a butcher’s shop and a haberdashery, away from mammon and into the calm coolness of the sahn, the forecourt of a 16th century mosque, where I left him to his prayers.

To a young student from the West, the teeming life and pageant of Istanbul was completely compelling and exotic – alive with the romance and allure of the orient. The city a palimpsest of the architecture, cultures and belief systems of its successive Eastern and Western masters; traces of the past shimmering just below the surface like coins in a fountain. Looking back, my exposure to the architecture, history and culture of Turkey was a critical part of my education in design. Experiencing its venerable coffee tradition was equally transformative: coffee suddenly became a rich and complex thing, volatile and of varying quality, something to seek, something to pursue. It was only much later that I realized just how venerable that tradition is, that in addition to algebra, trigonometry, and the underpinnings of scientific objectivity, the Golden Age of Islam also gave us coffee. As Paul Christopher Johnson writes in his remarkable essay on coffee:

“…from [coffee’s] emergence in Ethiopia to its systematic plantation in Yemen to its global transport via the expansion of Islam and then the Ottoman Empire, to the arrival in Europe via Turkey in the hands of Venetian traders, to the first coffeehouses of Europe by the mid-1600s.”

In the piece Johnson explores the idea of the godshot, I say idea because he defines it not as a specific recipe or format of coffee, but rather as an ideal: the perfect but ultimately unobtainable shot of espresso, tantalizingly close, perhaps just one bean or tweak or piece of equipment away, but always, finally, just beyond our reach because perfection is the purview of the gods and we who seek it mortal. It is the everlasting quest for the godshot, the naïve belief that the next coffee I make will be the perfect one, that distinguishes the obsessive from the merely enthusiastic coffee drinker.

“Anselm, [Archbishop of Canterbury from 1093 to 1109], defined God as a being than which nothing greater can be conceived. This is never the case for the ultimate demitasse of espresso, known as the godshot. Occasionally a godshot is reported, a triumph of technique, technology, and nature. But mostly godshot suggests deferral, a perfection yet to come.”

In the end it is the process of this constant search for perfection – the playful tinkering and adjustment followed by the test, the comparison to that ideal perfect cup we hold in our mind – that becomes the end rather than the means. The goal becomes not the perfect cup, but one that is better than the one before, inching ever closer to the asymptote of perfection. The cyclical negotiation between practice and performance is something we recognize in sports and music, but it also exists in disciplines that define themselves as practices like architecture, law and medicine. I would argue that it also extends to making things. Those who are the best at it are the ones who continually strive to deepen their understanding of their process, always reaching for the thing that is just beyond their grasp.

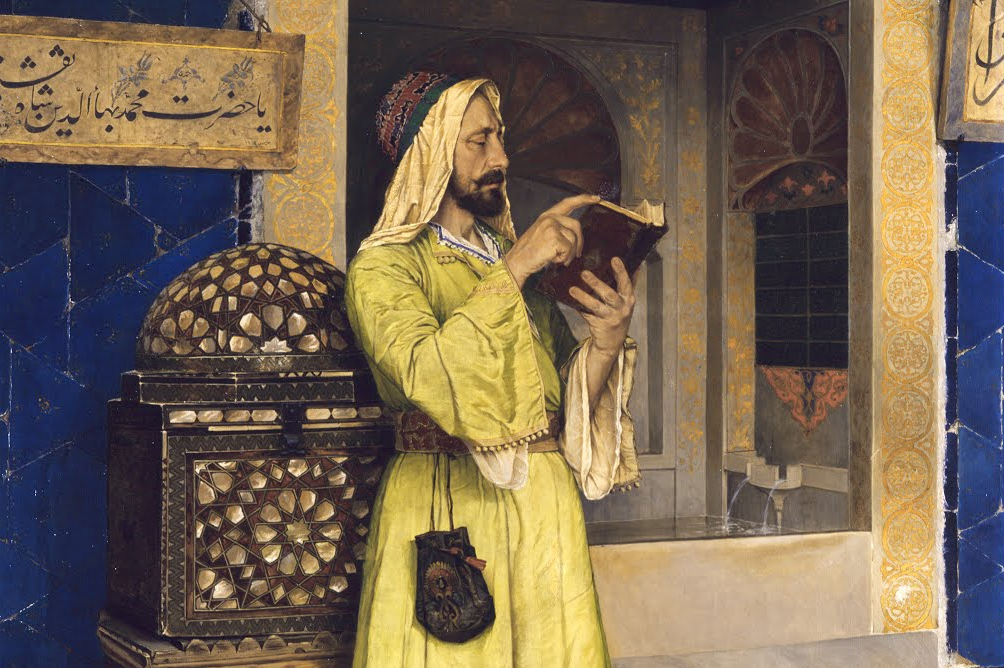

But back to where we left Aslan, washing at the fountain of the mosque before going to pray. In contrast to Western religious art, the Islamic design tradition is aniconic or non-figural, employing instead geometric or vegetal patterning and calligraphic ornamentation as its predominant means of artistic expression. Geometry and geometric patterns are considered sacred – a mirror of the infinite nature of Allah – each individual element part of a boundless whole. The design of mosques themselves might be vulgarized as the translation of these two-dimensional divine geometries into three-dimensional earthly form. And the architects of mosques would, I was told2, introduce a deliberate flaw into the “perfect” geometry of their plan, so as to appear humble before God. I don’t know if this is actually true, but I fervently hope so. In Greek tragedy, hubris is the crime of “excessive pride toward or defiance of the gods…”3 and it would seem that the avoidance of this crime was uppermost in the minds of the architects of Istanbul’s Ottoman masterpieces. At least it was important enough to them to risk offending their great and all-powerful patron:

A heavy iron chain hangs in the upper part of the court entrance on the western side of the Mosque. Only the sultan was allowed to enter the court of the Blue Mosque on horseback. The chain was put there, so that the sultan had to lower his head every time he entered the court in order not to get hit. It was done as a symbolic gesture, to ensure the humility of the ruler in the face of the divine.4

The path of the perfectionist is fraught with danger.

Which brings me to the end of this meandering digression through the streets of Istanbul and its imperious architecture and to a significantly smaller, far more prosaic totem of delayed perfection: the launch of the third “Constantinople” Edition5 of Lapera’s signature lever machine, the DS3. This release of 25 serial numbers, with a subtly re-engineered group and a myriad of other incremental improvements, is already in production and should ship, as always with the caveat of all being well, this winter. A number are already spoken for. The base price for the edition is $9717.17 USD plus actual shipping – roughly $650 to the US. You can reserve your serial number here. Once we receive confirmation from you we will be in touch to sort out the details, customization and to welcome you to Lapera.

Thanks for reading.

1 – the 19th century sort, not the Stigless one you have to go on after you punch your producer.

2 – Or at least so I was told by a luminary Virgil from the beneficent Purgatory that was my post-secondary education.

3 – Oxford Languages

4 – The Architecture of the Blue Mosque

5 – The first, Founders’ Edition machines, are the Rumsfelds, the second never received a name because the “Small Village Edition” seemed not quite right somehow.