Some say that he spends three hours a day staring directly into the sun and that his

visor is actually entirely opaque. All we know is that he is called the sTIG.

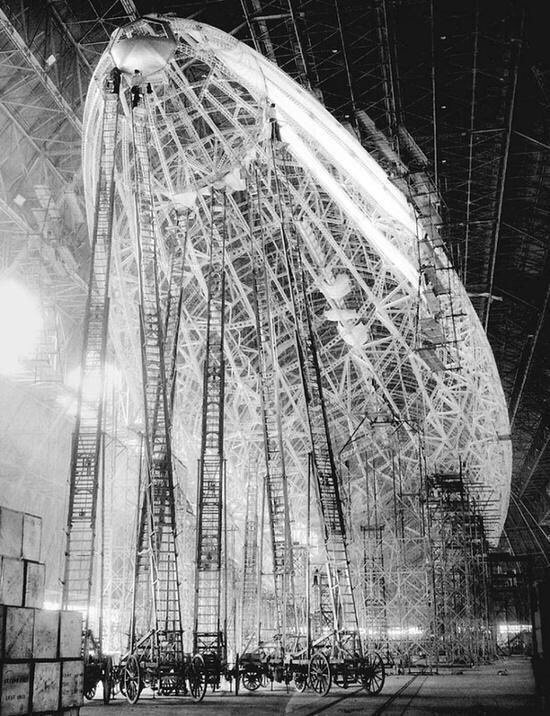

This series of posts is about invisible updates to a largely invisible part of the machine: the boiler. This particular upgrade however, is both the invisibilest and the most important: the person doing the welding. I’ve said elsewhere that welding is both a skill and an art. Like very few other industrial activities, welding, especially TIG welding, is a manual skill akin to playing an instrument that requires both talent and vast amounts of practice. There are good welders and bad welders and the latter vastly outnumber the former.

I am a passable welder. I, at least, know what is supposed to happen, what is not supposed to happen and how, in theory, to achieve / avoid both. The execution, on the other hand, is a different story. Malcolm Gladwell1 introduced the idea of the 10,000 rule hour in his hugely popular (in both senses of the word) 2008 book Outliers. The precis: the greatest are great at what they do because of talent, opportunity but mostly because they spent at least ten thousand hours mastering their craft2.

In welding, the 10,000 hour rule applies. I break out the welding equipment perhaps once a month for small jobs and a once or twice a year for more extended sessions. I took one welding course once upon a time over a summer while I was at university. I didn’t spend years learning the craft as an apprentice to a master welder and I haven’t spent the three hours a day for ten years practicing to develop and maintain the skills required for TIG welding. This occasional use makes me an amateur as opposed to a professional, a Sunday painter as opposed to a Jackson Pollock and a Sunday driver next to the sTIG.

The Lapera workplace, while sometimes intense, tends not to be over-populated with people who punch other people when they don’t get a hot dinner. We will also depart slightly from British Motoring Television tradition by naming the man behind the helmet: Martin Berthelot is a professional welder. And rather a good one. In fact, an insanely good one. And it is he, as opposed to me who will be welding the Lapera boilers.

So let’s see how our very own sTIG handles Hammerhead and Gambon.

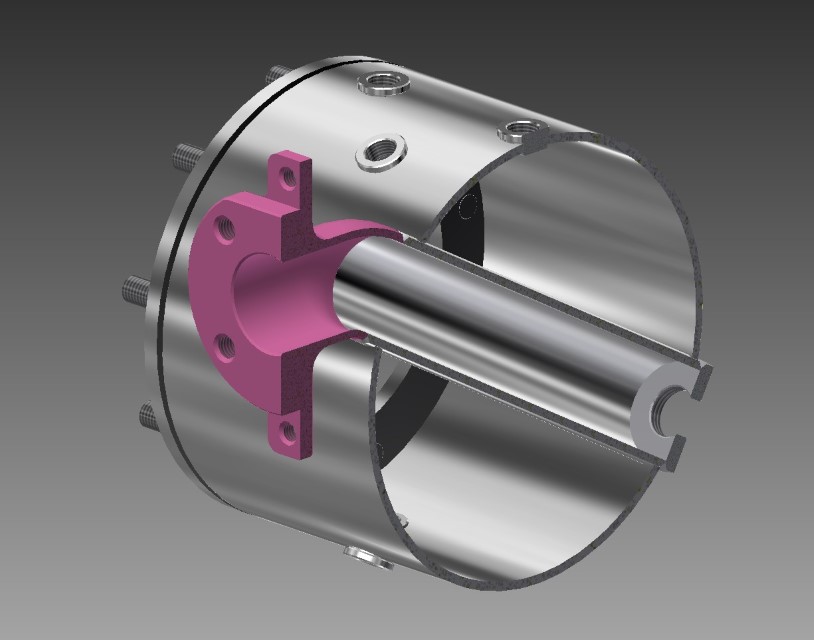

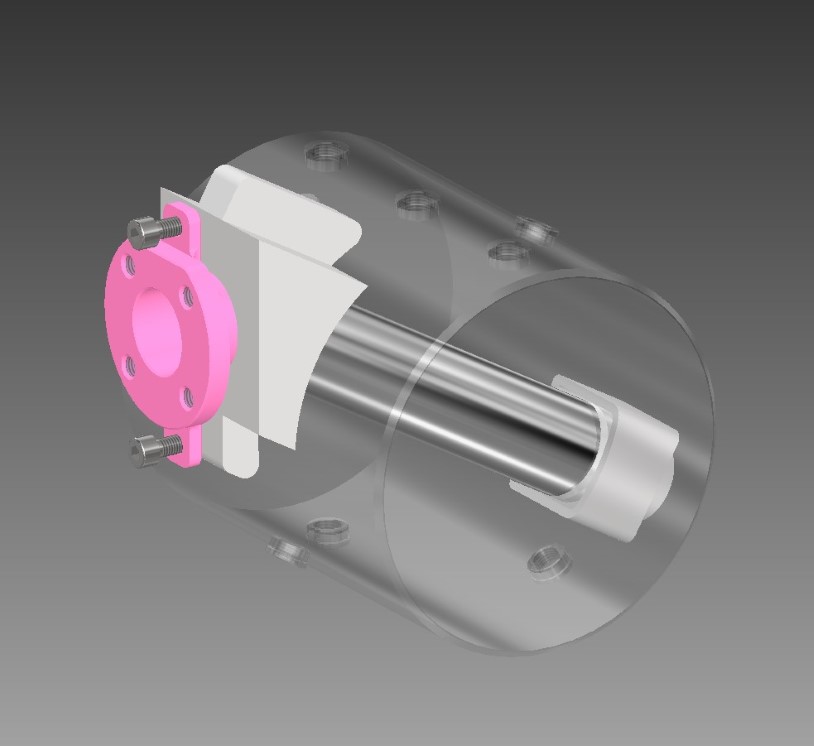

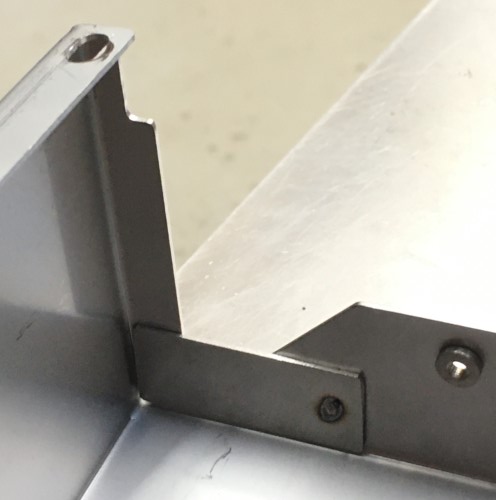

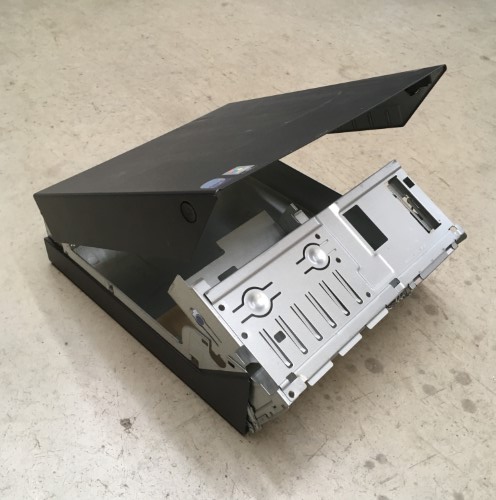

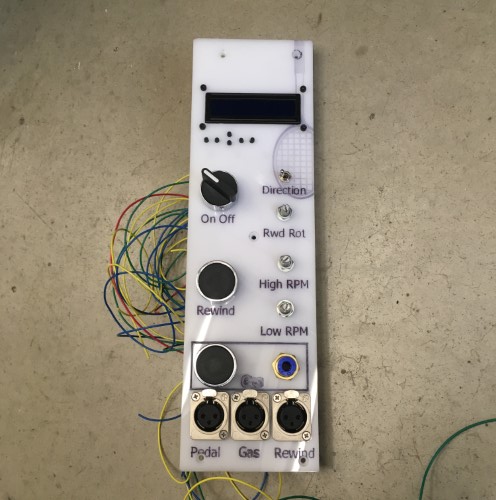

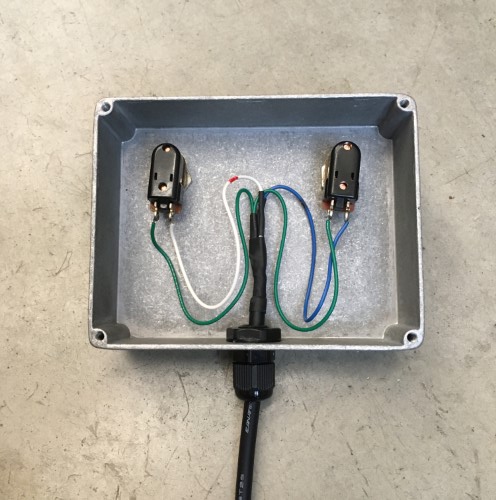

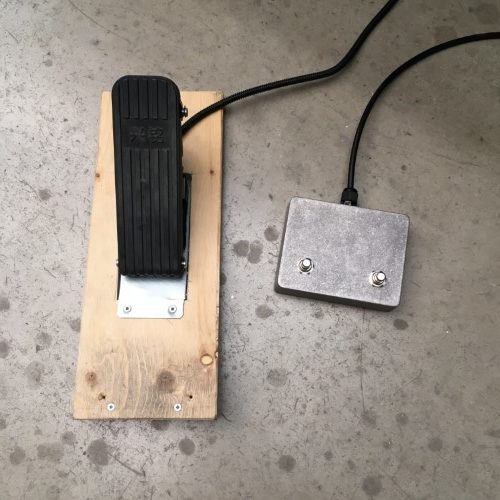

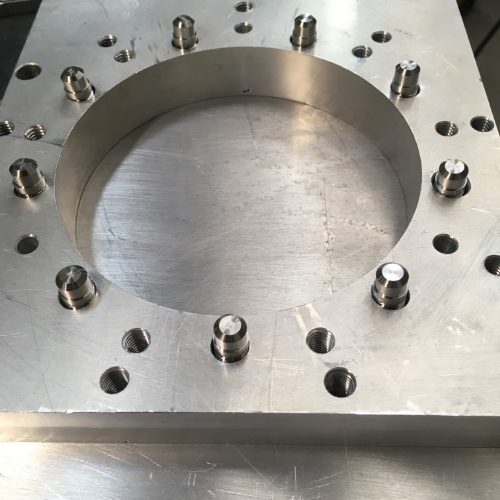

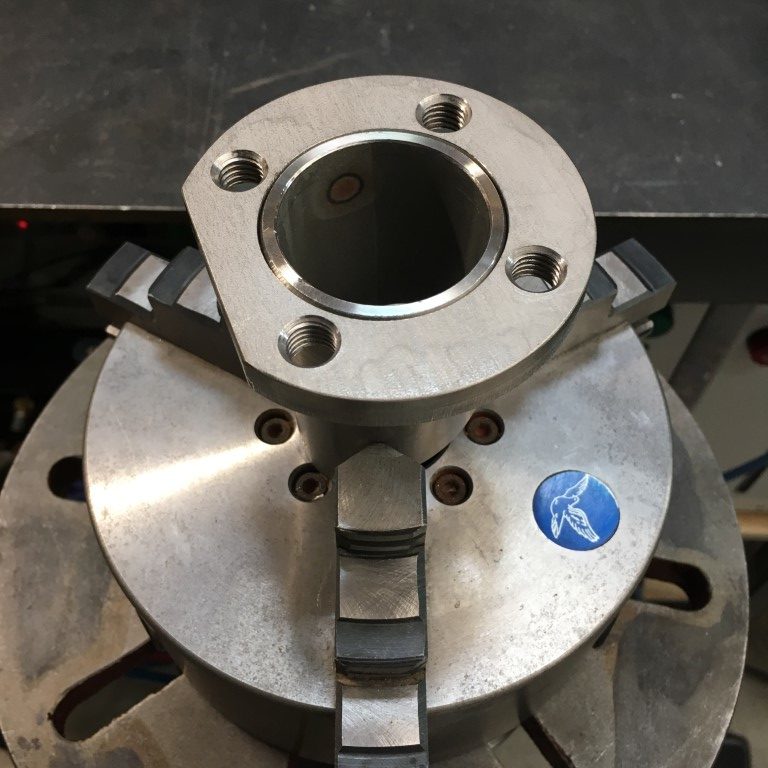

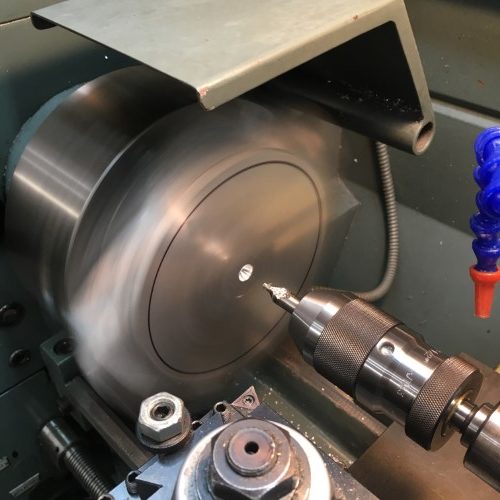

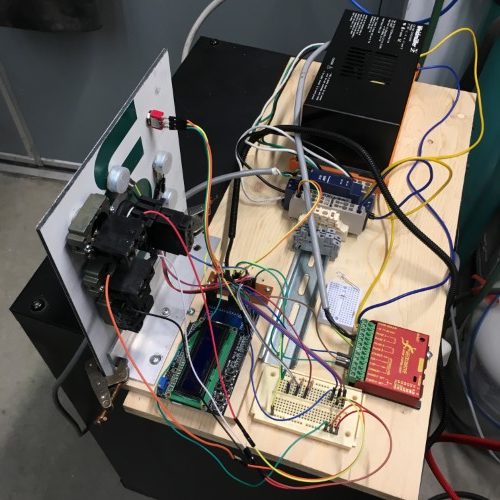

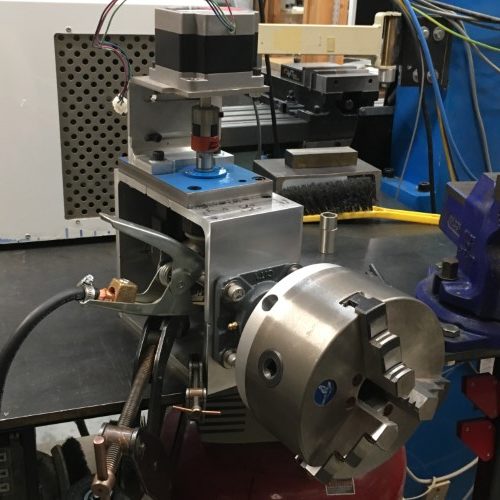

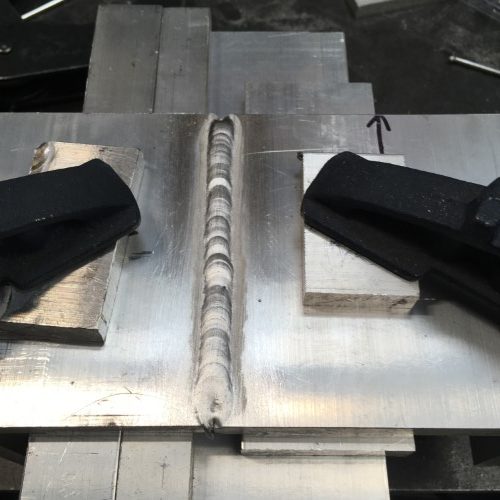

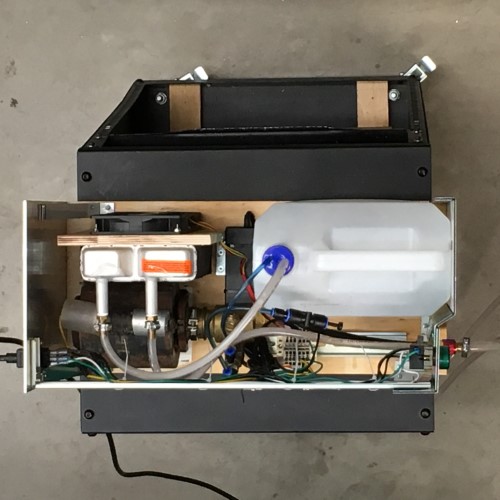

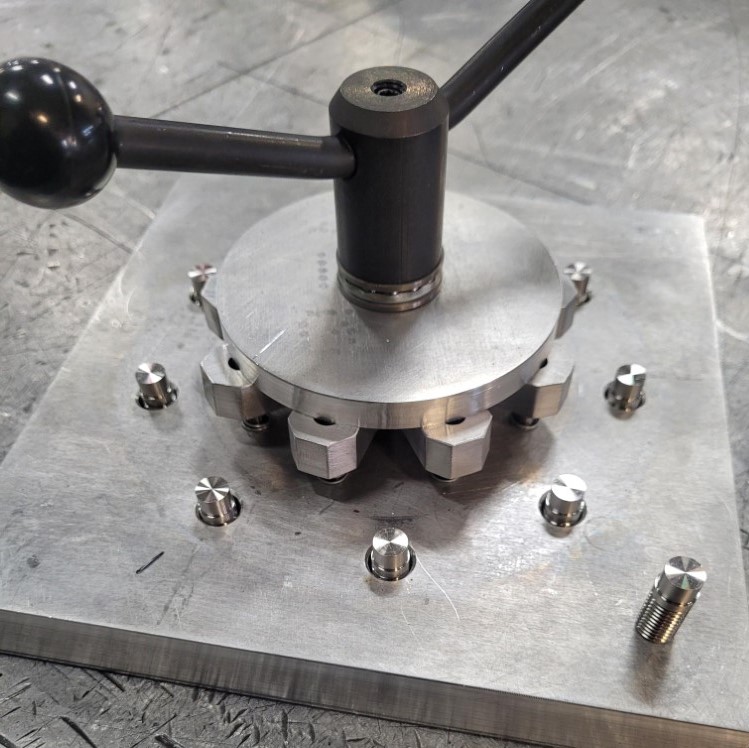

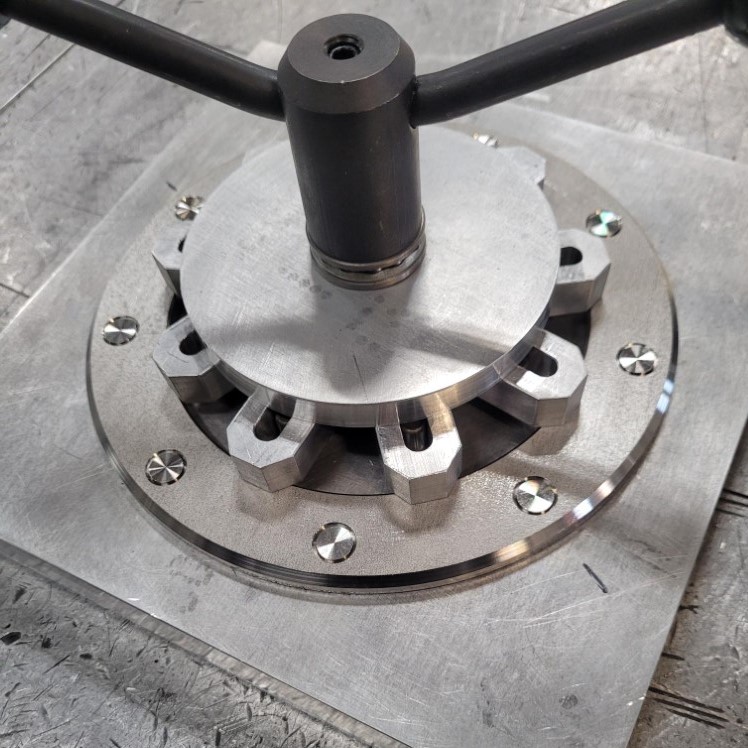

First things first: the bolt rings that hold the end plates and seals in place – important, you know, for keeping the water in the boiler. For this, of course, we built a jig. And a very fancy one at that. The shoulders of the bolt studs need to be held up against against the ring from the underside – so the pockets that they sit in are spring-loaded.

And then the best bit: the fingers that hold the ring down extend and retract to allow the ring to be installed and removed after welding.

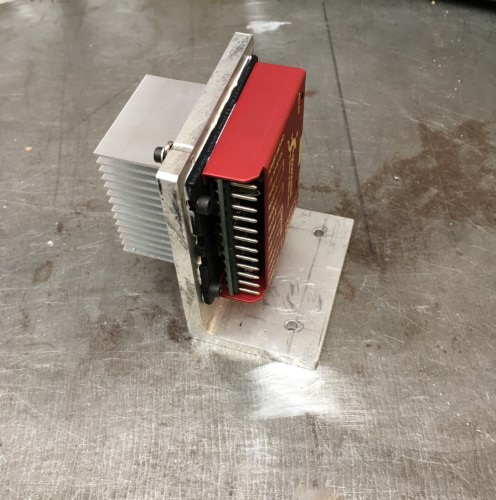

Finally, the screw is tightened with the giant handle (with a thrust bearing to manage the considerable load) and forces everything down onto the aluminum heatsink in order to draw away the distortion-inducing heat as quickly as possible after the completion of the weld.

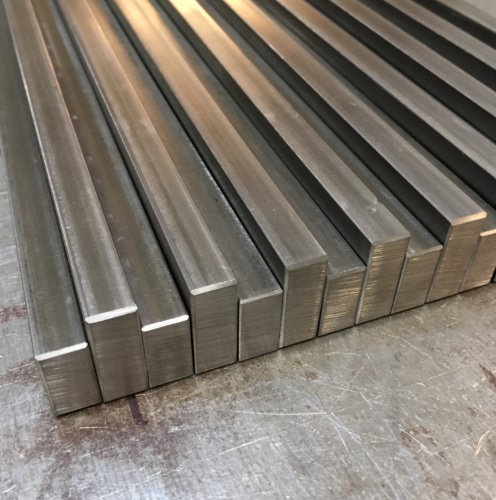

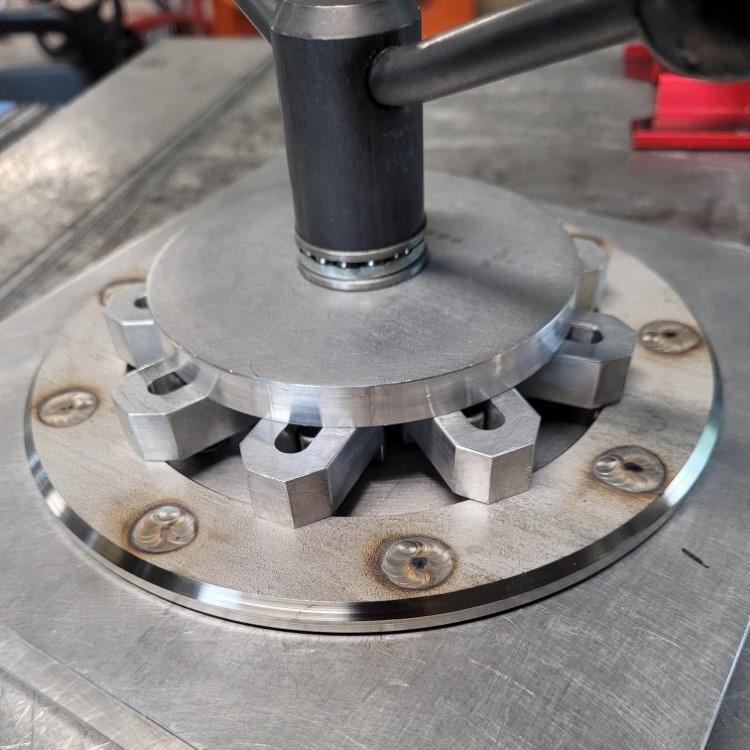

And look at that: loads of wheelspin off the line (and barely any HAZ (Heat Affected Zone)) as the sTIG powers down the straight towards the first corner.

Perfect overlapping fish scales with almost no coloration of the weld bead. Mindboggling control.

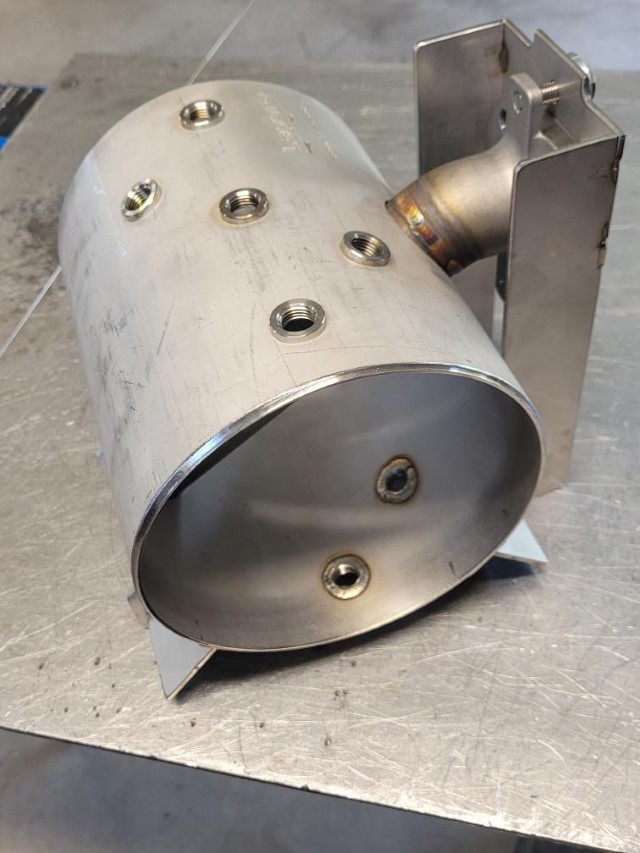

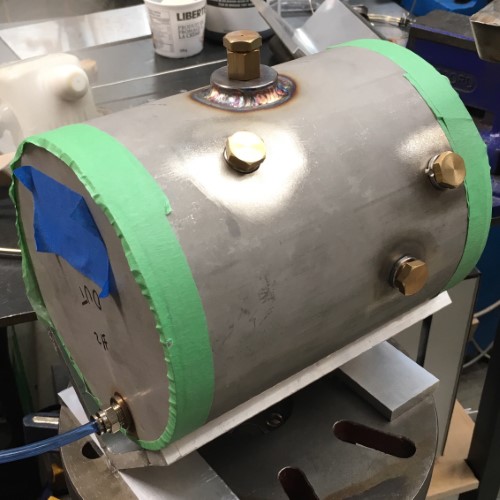

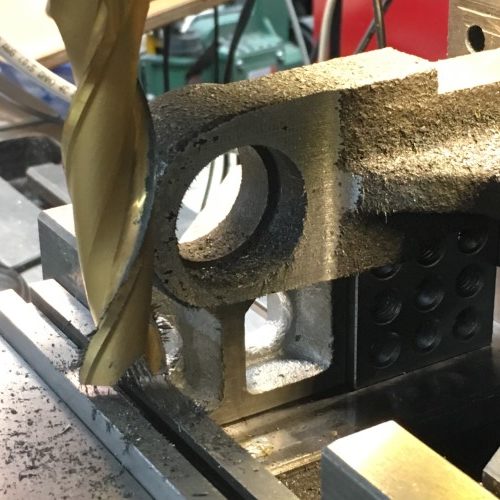

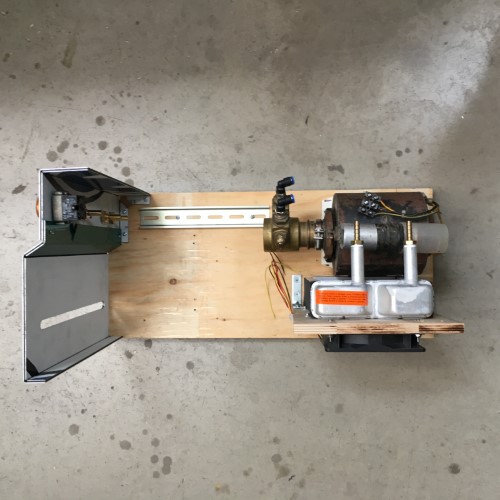

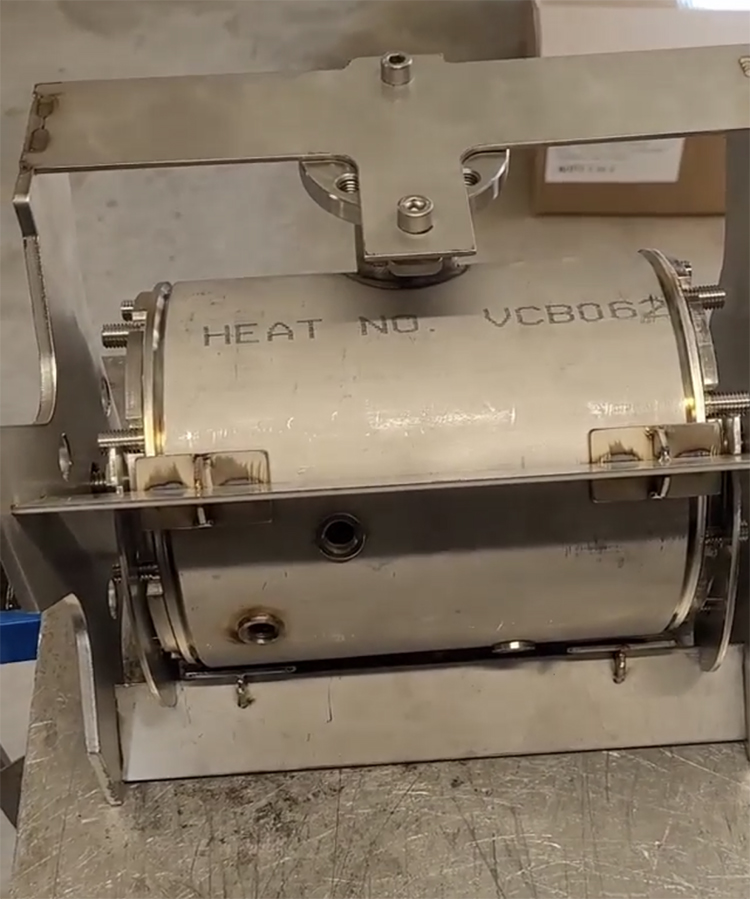

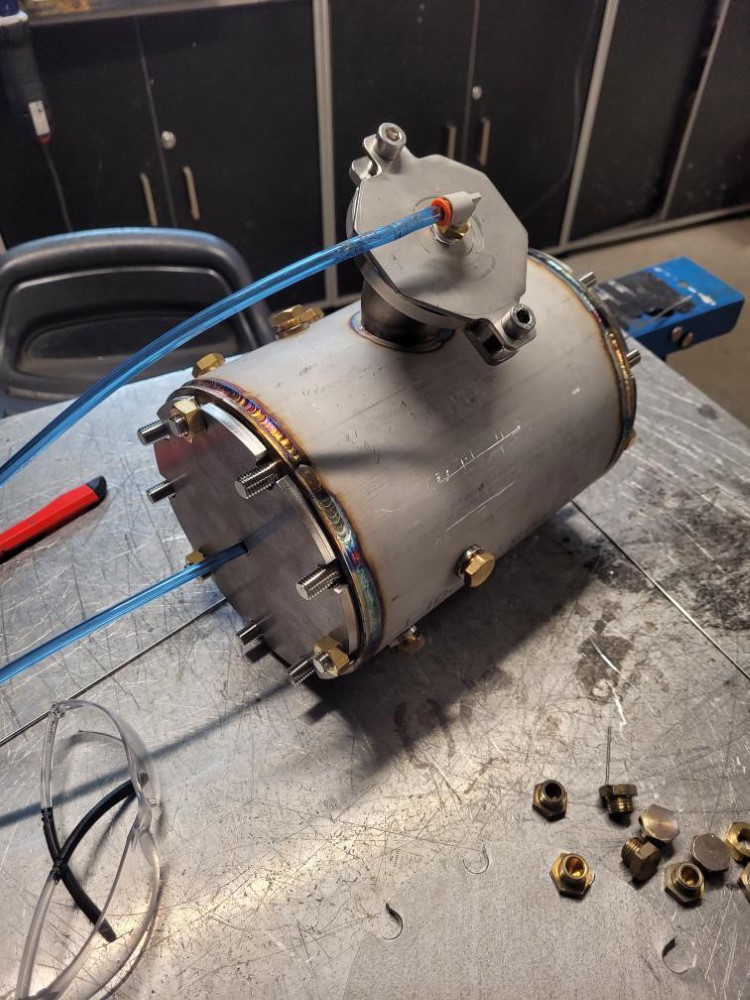

The next step is to complete another sub-assembly – or sub-weldment: the heat exchanger (HX). The HX is comprised of a 316L stainless casting and a capped 316L tube. The casting replaces a far more complicated weldment which was a composite of five separate parts. Simpler is (almost) always better.

The sTIG handles the oversteer going into the first corner with aplomb delivering an impeccable “full-penetration” weld, so-called because the material of the parts is melted all of the way from the outside to the inside and is mixed with “fresh” filler rod material to create a perfect corrosion-resistant weld.

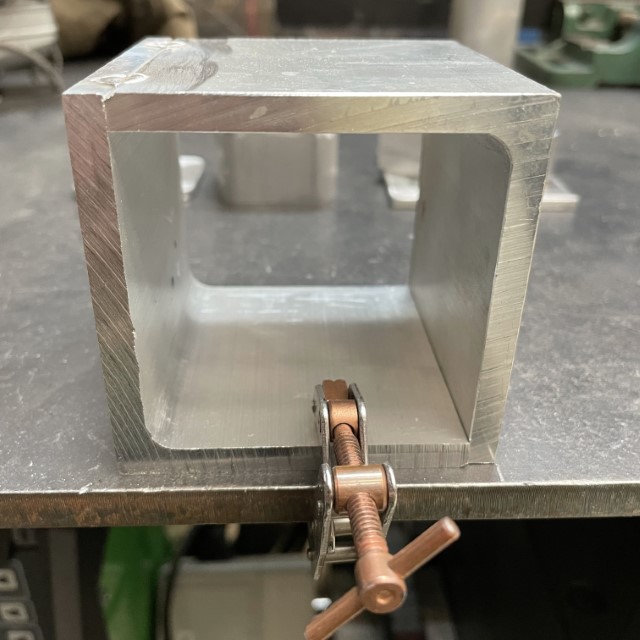

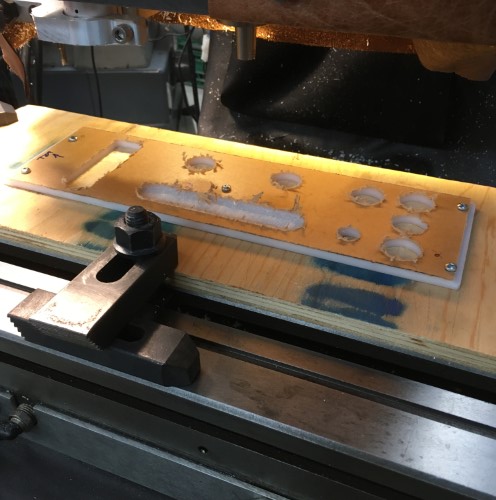

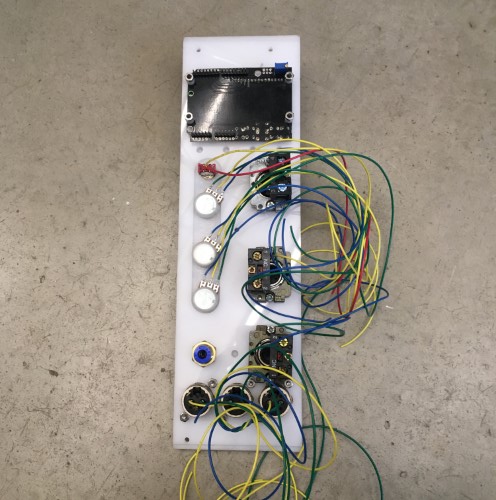

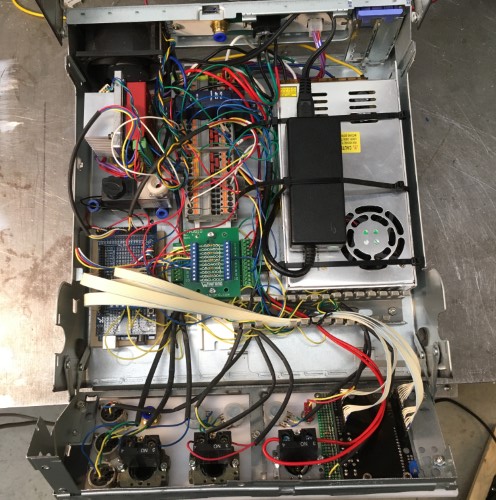

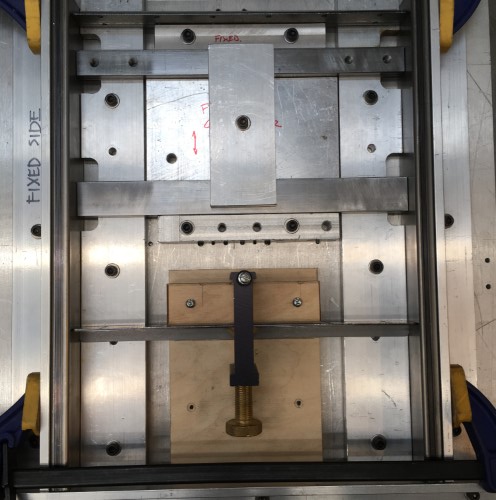

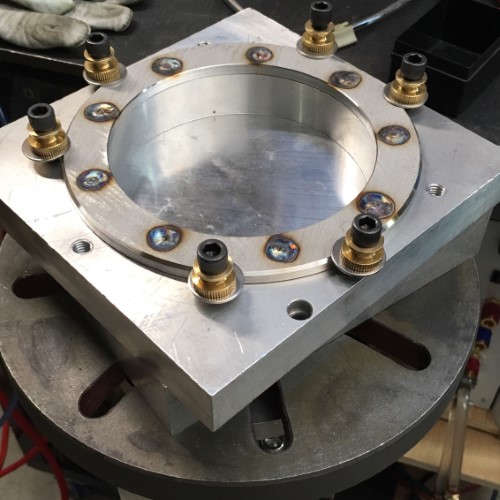

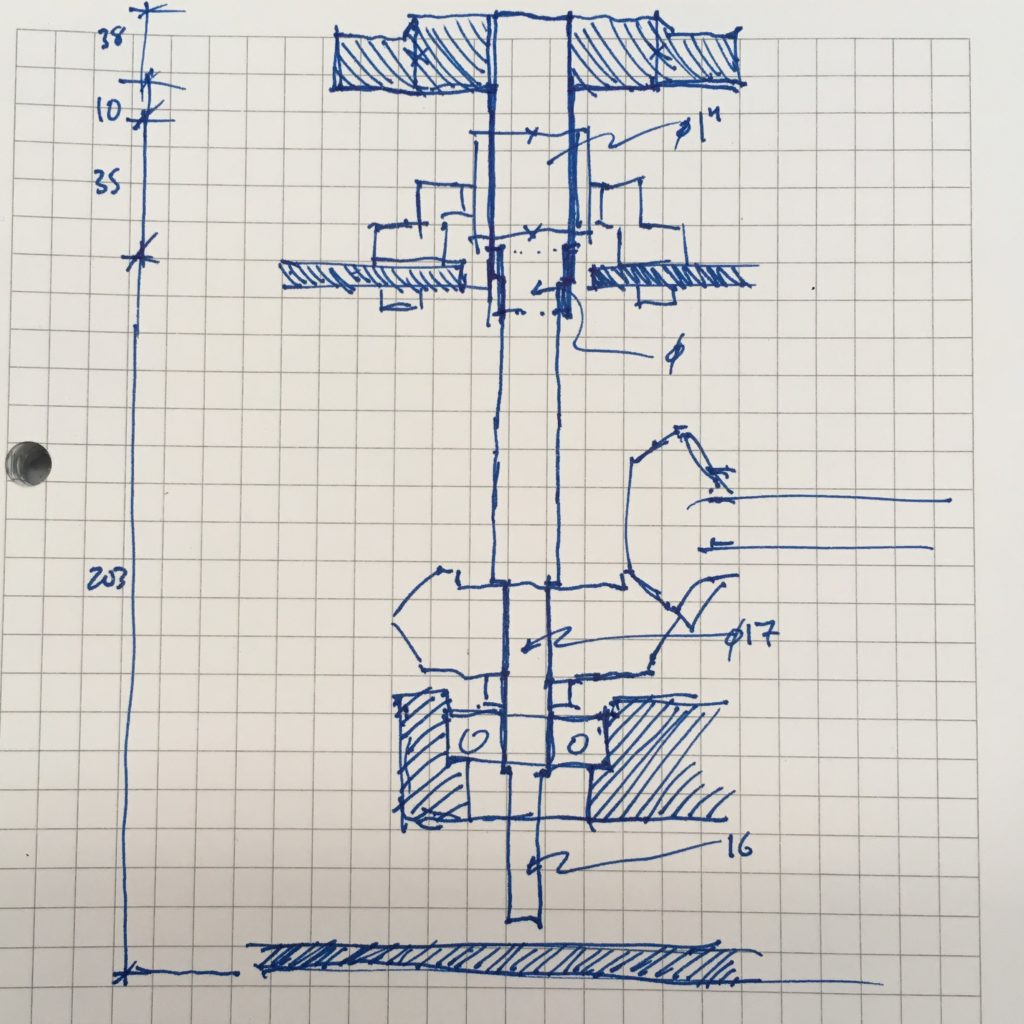

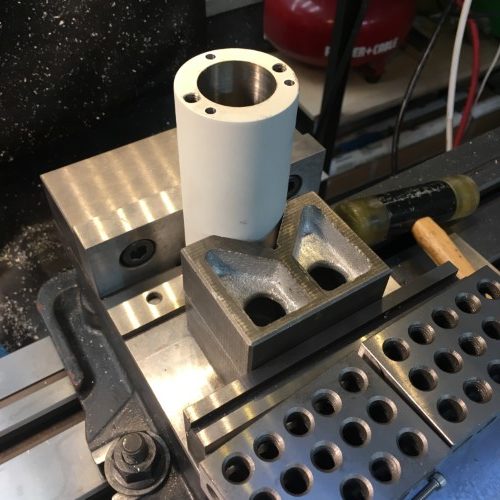

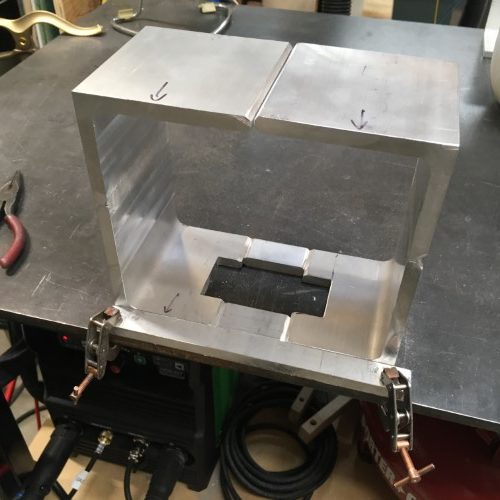

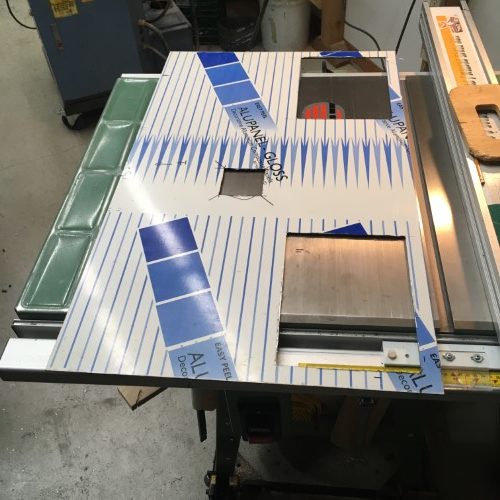

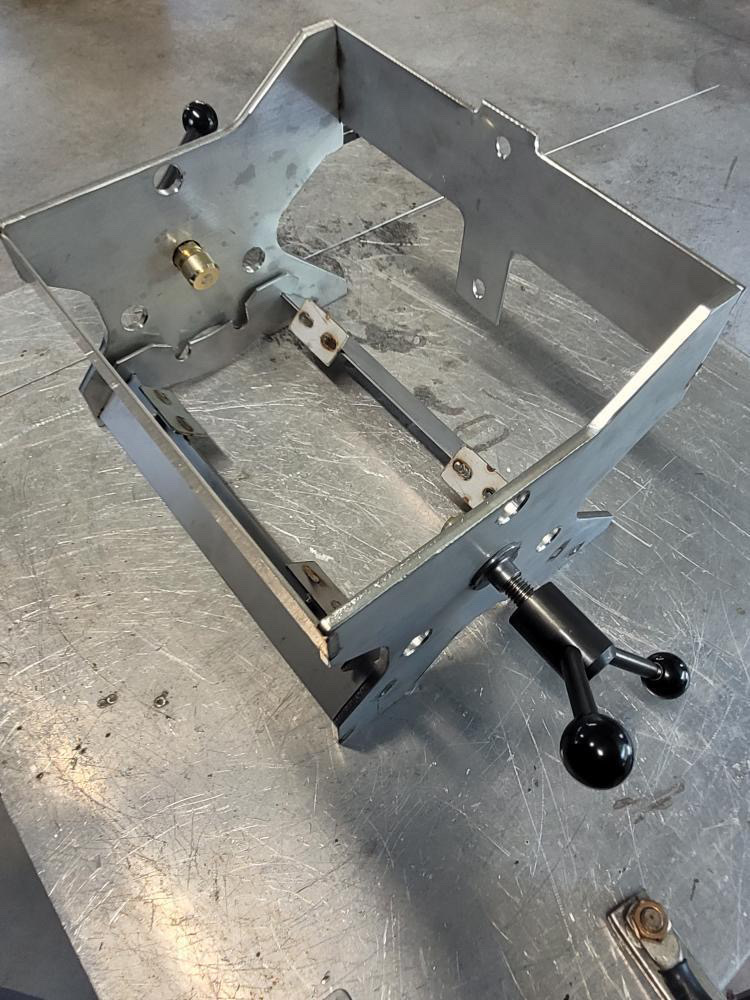

Now we move onto another jig, affectionately known, for reasons that will no doubt be apparent to the knowledgeable readers of this humble blog, as “The Slayer“.

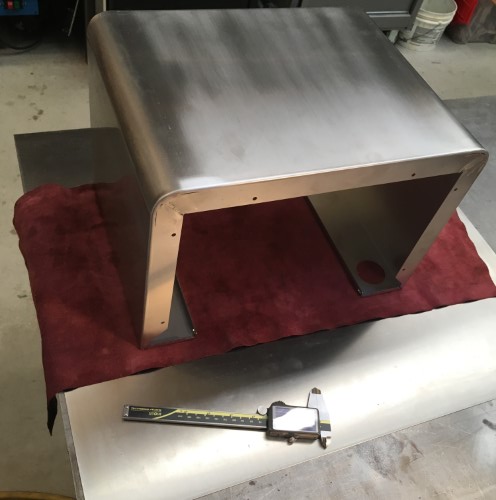

This jig does double duty for the fairly complex task of alignment and clamping for positioning the bolt rings at both ends of the main boiler tube.

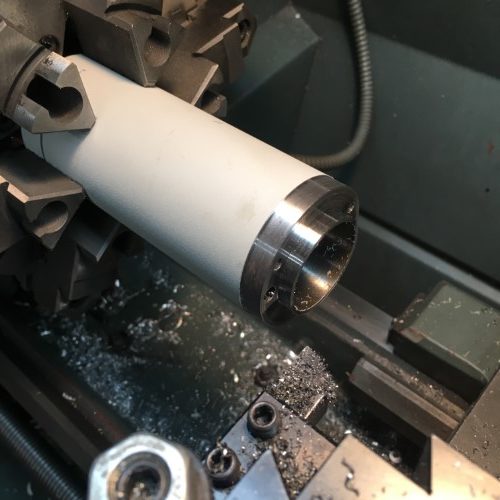

And down into Hammerhead, the trickiest corner on the track, with the argon gas purge lines in place the sTIG is feathering the throttle to achieve the delicate balance between weld penetration and heat input.

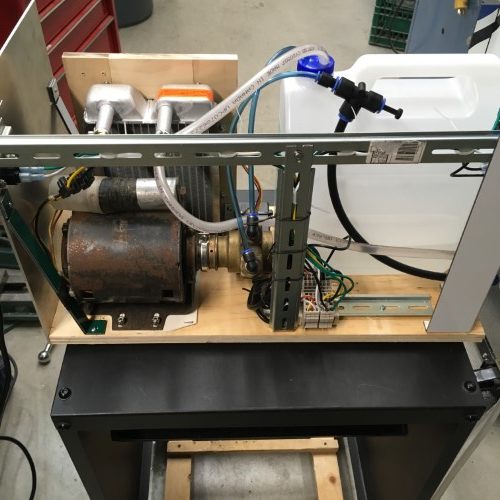

Heading into Gambon then, the sTIG is making it look easy. In fact, this one, the interior junction of the HX and main boiler tubes, is really off-the-charts crazy. This weld is performed inside the boiler tube. I don’t know, I can barely get my hand inside, let alone weld in this space and the sTIG is not a small man (but he does have small children. Hmmmm.) Not only that, but some parts of the weld are not visible while you are welding, even if you use a mirror (in which case you have to weld upside-down and backwards – ever tried cutting your own hair in the mirror?). Judging only from the intensity of the light given off by the weld arc hidden around the corner, the sTIG can actually weld blind.

And he’s across the line. Here is the grand tour of the main boiler, welded entirely from the inside to minimize corrosion.

At the risk of overextending my professional racing driver metaphor, every corner on a race track is distinct and is more or less difficult, requiring a particular approach speed, breaking point, line through it etc. It is the sum of the driver’s successes (and failures) in the individual corners that make up the overall time for the lap. A mistake on any one of the corners results in either a bad time or going off the track. The welding here is also a sequential process. The individual welds, none of which can be regarded as particularly easy, are performed one after another. A mistake on any one of them will ruin the part. High stakes indeed. Fortunately for us, the sTIG is a consummate professional.

1 – Not quite an apologist for laisse-faire industrial capitalism, but almost?

2 – Others have since argued, compellingly in my opinion, that the fourth ingredient is the quality of instruction. What and how you practice during those 10,000 hours turns out to be, unsurprisingly, important.